Automatic and manual transmissions are built to survive years of abuse, yet the same internal parts tend to fail first when fluid breaks down, heat builds up, or drivers ignore early warning signs. Knowing which components most often need replacement helps me spot problems sooner, budget realistically, and decide whether a repair or full rebuild makes more sense.

Instead of treating the gearbox as a mysterious sealed box, I look at it as a collection of wear items, much like brake pads or tires. Clutches, bands, solenoids, seals, and sensors all have predictable lifespans, and when they start to go, they leave a trail of symptoms that good reporting and technical documentation have mapped out in detail.

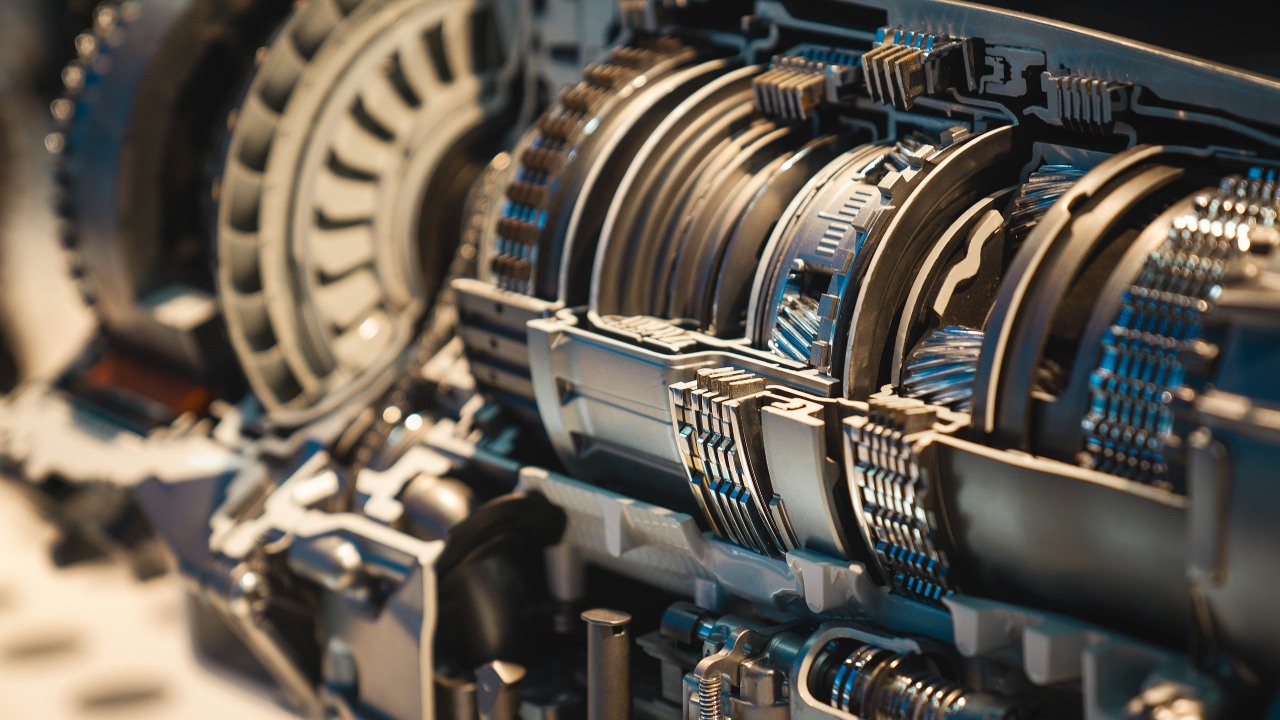

Clutch packs and friction plates: the transmission’s primary wear items

Inside most automatic transmissions, multi-disc clutch packs do the same job as a manual clutch, engaging and releasing to select gears, and they are among the first parts to wear out. Each pack stacks steel plates with friction-lined discs, and every shift rubs those surfaces together, slowly thinning the friction material until it slips, overheats, and contaminates the fluid with fine debris. When I see delayed engagement into Drive, a flare in engine rpm between shifts, or a harsh bang into gear, worn clutch packs are usually at the top of the suspect list, especially on high-mileage units that have gone too long between fluid changes.

Heat is the enemy here, and it builds quickly when a vehicle tows heavy loads, sits in stop‑and‑go traffic, or runs with low or dirty fluid. Once the friction material starts to burn, the fluid darkens and takes on a sharp, burnt odor, and that contaminated oil then accelerates wear on other internal parts. In many late‑model automatics, including popular units in vehicles like the Toyota Camry and Ford F‑150, technicians often replace entire clutch packs during a rebuild rather than trying to salvage partially worn discs, because mixing old and new frictions can lead to uneven engagement and repeat failures. When the damage is caught early, a targeted overhaul of the affected clutch packs can restore crisp shifting, but if the debris has circulated for too long, it usually makes more sense to replace all the friction elements at once so the transmission has a fresh baseline.

Bands, drums, and servos that control gear changes

Where clutch packs handle many shifts, some automatics also rely on steel bands that cinch around rotating drums to hold parts of the gearset stationary. These bands are lined with friction material similar to clutch plates, and they wear in the same way, especially if the transmission is repeatedly forced to kick down under heavy throttle or if the band adjustment drifts out of spec. When a band starts to fail, I often see symptoms limited to one or two gears, such as a missing second gear or a pronounced slip only on a particular upshift, because each band is tied to specific gear ranges.

The hardware that applies those bands, usually servos and pistons, can also become problem parts that need replacement. Hardened seals, scored servo bores, or cracked apply pistons reduce the clamping force on the drum, which shows up as a soft, drawn‑out shift or a flare in engine speed before the gear finally engages. In classic rear‑wheel‑drive units like the General Motors 4L60‑E, worn 2‑4 bands and their servos are notorious failure points, and rebuild kits routinely include new bands, apply pins, and servo seals as standard replacement items. When I evaluate a transmission with band‑related issues, I rarely stop at the friction surface alone, because the surrounding hardware often shares the blame and needs to be renewed at the same time.

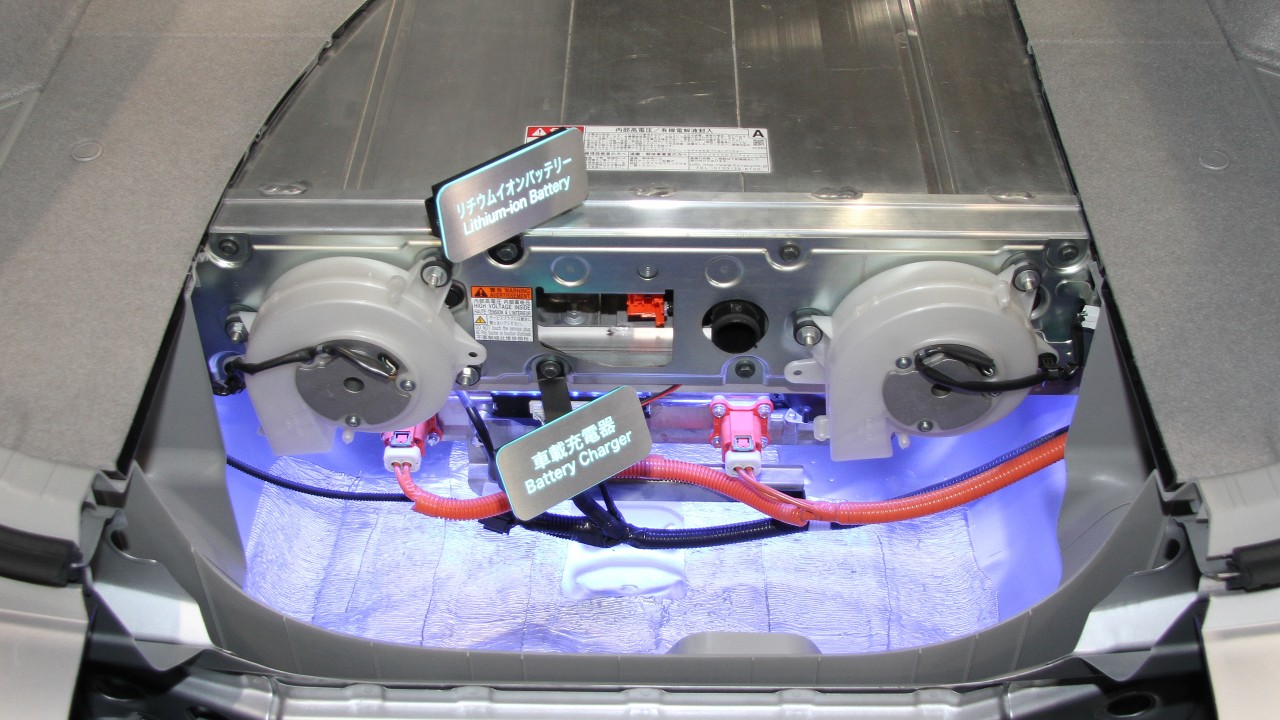

Valve bodies, solenoids, and electronic control components

Modern automatics depend on a complex hydraulic brain called the valve body, along with a network of electronic solenoids, to route pressurized fluid and time each shift. Over time, the tiny passages in the valve body can wear or clog with varnish and debris, and the solenoids that open and close those passages can stick or fail electrically. When that happens, the transmission may slam into gear, hesitate before shifting, or default into a single “limp” gear to protect itself, and the fix often involves replacing individual solenoids or the entire valve body assembly.

Because these parts sit in hot, constantly circulating fluid, they are especially vulnerable when owners skip fluid changes or use the wrong specification. In many late‑model vehicles, including continuously variable transmissions and dual‑clutch units, the control system is even more tightly integrated, with mechatronic modules that combine electronics and hydraulics in one housing. When those modules fail, they are usually replaced as a unit rather than repaired on the bench, which can turn what looks like a minor shifting quirk into a four‑figure repair. I pay close attention to diagnostic trouble codes, line‑pressure readings, and commanded versus actual gear data, because those electronic breadcrumbs often point directly to a failing shift solenoid, pressure control solenoid, or valve body that has become a common replacement item on high‑mileage cars.

Seals, gaskets, and torque converter failures

Even when the hard parts inside a transmission are healthy, the soft parts that keep fluid contained and pressure stable are constant wear items. Rubber and synthetic seals harden with age and heat, gaskets shrink or crack, and the result is fluid leaks at the pan, input shaft, output shaft, or cooler lines. A slow leak might start as nothing more than a few drops on the driveway, but as the fluid level falls, the pump begins to draw air, pressure drops, and clutches or bands start to slip, which quickly turns a cheap seal replacement into a full rebuild. That is why I treat any unexplained drop in fluid level or fresh stain under the car as a warning that a seal or gasket is ready for replacement.

The torque converter, which couples the engine to the transmission in most automatics, is another frequent replacement part once mileage climbs. Inside the converter, a lockup clutch engages at cruising speeds to reduce slippage and improve fuel economy, and that clutch can wear or glaze just like internal friction plates. When it fails, drivers often notice a shudder at highway speeds, a surge in engine rpm without a corresponding increase in road speed, or contaminated fluid filled with fine metallic dust. Because the converter is welded shut and difficult to service, shops typically replace it outright whenever there is evidence of internal damage or when a transmission is being rebuilt for other reasons. I have seen many cases where ignoring an early converter shudder allowed debris to circulate long enough to damage the front pump and input shaft seals, turning a relatively contained problem into a much larger repair.

Manual transmission clutches, synchronizers, and related hardware

Manual gearboxes have fewer moving parts than automatics, but they still have predictable failure points that show up again and again in repair records. The most obvious is the clutch assembly itself, which includes the friction disc, pressure plate, and release bearing. Aggressive driving, frequent stop‑and‑go use, or towing can wear the clutch disc down to the rivets, leading to slip under load, a burning smell, or a high engagement point on the pedal. When I see those signs on vehicles like the Honda Civic, Subaru WRX, or Ford Mustang, I know a clutch kit is likely in their future, and it is standard practice to replace all three components at once rather than trying to reuse a tired pressure plate or noisy release bearing.

Inside the manual transmission, synchronizer rings and hubs are the parts that most often need replacement, especially on cars that have seen a lot of hard shifting. Synchronizers match the speed of the gears before they engage, and when their friction surfaces wear out, the gearbox starts to grind when shifting into specific gears, usually second or third. Drivers may also notice that the shifter pops out of gear under load, a classic sign that the engagement teeth and synchro assemblies are worn. During a rebuild, I typically see new synchronizer rings, bearings, and seals included as standard replacement items, because once the gearbox is open, it is cost‑effective to refresh all the common wear parts rather than risk another teardown later. On some performance models, owners also upgrade to stronger aftermarket synchros or shift forks to address known weak points that factory parts have shown over time.

Leave a Reply