The 1974 Lamborghini Countach did not simply arrive as another fast Italian exotic. It landed like a design shockwave, turning the chaos of radical engineering, awkward ergonomics, and production compromise into a shape that still defines what a supercar looks like. By pushing form and function to their breaking points, the early Countach transformed drama into a coherent visual language that continues to echo through every wedge-shaped performance car that followed.

Rather than smoothing away its conflicts, the first production Countach made them visible, from its impossible sightlines to its theatrical scissor doors. That tension between purity and excess, between race-car aggression and road-car reality, is what turned the 1974 model into a design milestone rather than a museum curiosity.

The leap from prototype fantasy to 1974 reality

When Lamborghini moved from the early prototype to the 1974 production car, it was trying to translate a rolling design manifesto into something that could be built, sold, and driven. The prototype that appeared in the spring of 1973 was a research tool as much as a showpiece, a low, flat wedge that treated aerodynamics and packaging as an experiment rather than a settled science. That car previewed the basic stance, the cab-forward proportions, and the scissor doors that would define the Lamborghini Countach, but it did so in a way that treated practicality as an afterthought.

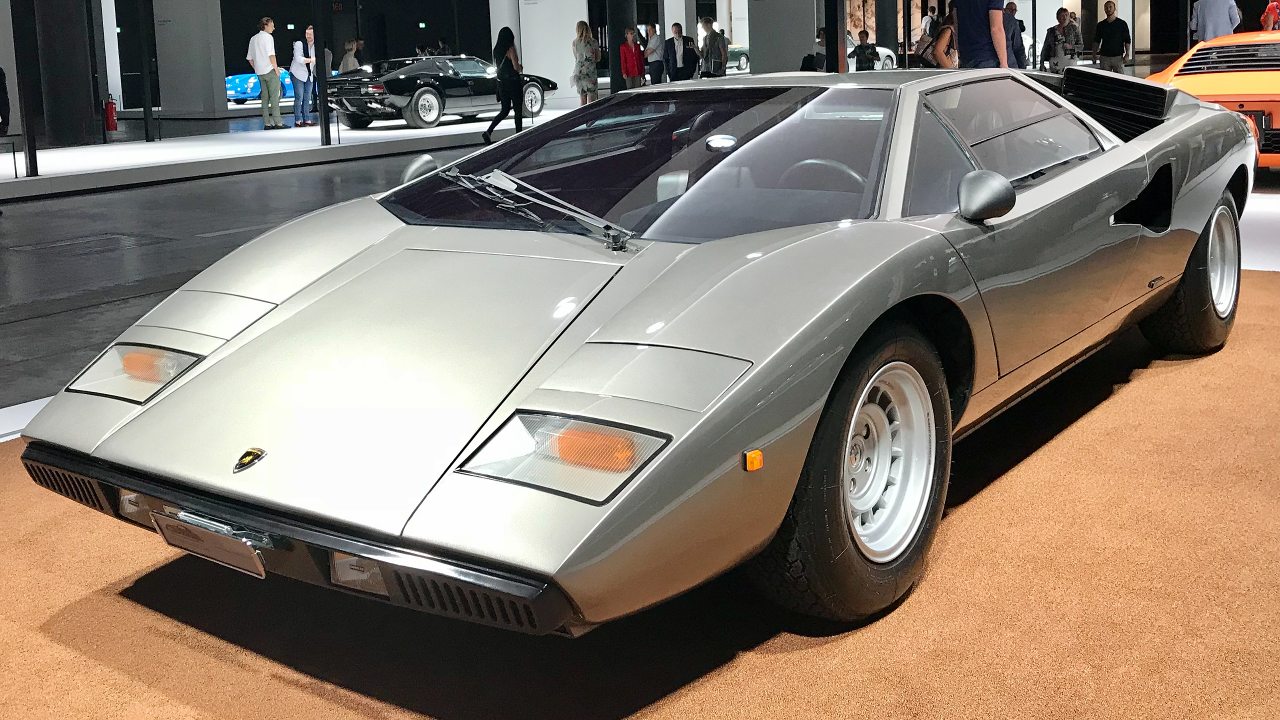

The production LP 400 that followed kept the drama but had to survive homologation, cooling demands, and real-world use. According to Lamborghini, the first version of the Countach, the LP 400 built between 1974 and 1978, was limited to 152 units, a figure that underlines how close it remained to a concept car in spirit. The company notes that this early 400 series wore fenders without extensions and a clean, uninterrupted body side, details that preserved the purity of the original wedge even as engineers reworked the chassis and mechanicals to cope with heat, noise, and durability. The shift from prototype to road car did not dilute the idea so much as crystallize it into a template for future supercars.

A wedge that redefined the supercar silhouette

The 1974 Lamborghini Countach is widely credited with redrawing the outline of the modern supercar. Instead of the flowing curves that had dominated the 1960s, it presented a sharp, geometric wedge, with a low nose, a steeply raked windshield, and a roofline that seemed to run in a straight line to the rear deck. Contemporary analysis describes the Countach as a revolutionary design that redefined what a high performance car could look like, emphasizing that it was not only visually radical but also a functional attempt to manage airflow and stability at speed.

The Countach’s journey is often described as proof of Lamborghini’s adventurous approach to supercar manufacturing, and the 1974 LP 400 is where that journey truly begins. The car’s wedge-shaped silhouette, combined with its mid-engine layout and wide rear track, created a stance that made it appear as if it were breaking speed records even when parked. Later retrospectives on the model’s evolution argue that this first production version captured the essential proportions that would influence not just subsequent Lamborghinis but an entire generation of performance cars, from later V12 flagships to rivals that adopted similarly low, angular profiles.

Drama in the details: scissor doors, periscope roof and “inconvenient ideals”

If the overall shape of the 1974 Countach set a new template, the details turned it into rolling theater. The scissor doors, which pivoted upward from the front hinge, were more than a party trick. They allowed access in tight spaces and worked around the very high sills and wide side structures required by the mid-engine layout. Reports on the car’s design history emphasize how these doors, combined with the rocket-ship-like rear end, made the Countach look futuristic from the very beginning, a quality that helped cement its status as a poster icon for decades.

The LP 400 also introduced one of the model’s strangest and most telling features, the so-called “periscope” roof channel that gave the early Countach its nickname. Lamborghini notes that this recessed section in the roof was intended to improve rear visibility by creating a visual tunnel to the back of the car, a solution that was as much a design flourish as a practical aid. Later commentary on the Countach’s ergonomics describes the car as an “inconvenient ideal,” a phrase that captures how the designers were willing to accept awkward sightlines, cramped space, and challenging ingress in order to preserve the purity of the wedge and the drama of the scissor doors. The result was a car that felt more like a piece of architecture than a conventional vehicle.

Quirks, compromises and the cult of cool

Living with a 1974 Countach was, and remains, an exercise in compromise, yet those compromises are a key part of its appeal. Owners and enthusiasts often point to the car’s notorious visibility issues, heavy controls, and heat-soaked cabin as evidence that it was engineered with aesthetics and speed as the top priorities. One detailed breakdown of the model’s quirks highlights “An Uncompromising Window Design” as one of the defining traits of the Countach, noting that the tiny roll-down section and fixed glass were direct consequences of the extreme door and roof geometry. The same analysis lists “One of the Countach” most iconic features as also one of its biggest usability challenges, underlining how the design refused to bend to everyday convenience.

Yet that refusal is precisely what has made the car a cult object. In enthusiast communities, the Lamborghini Countach is often described as “just plain cool,” even when compared with newer supercars that are faster, more powerful, and more reliable. The car’s quirks, from the need to sit on the sill and reverse with the door open to the way the cabin wraps tightly around the driver, are treated less as flaws and more as rituals that connect the owner to the machine. This attitude aligns with broader historical overviews that frame the Countach as a “design revolution,” arguing that its willingness to prioritize visual impact and emotional response over comfort helped define the supercar as an object of desire rather than a rational purchase.

From Sant’Agata to the supercar canon

The 1974 LP 400 did not remain frozen in time. As production continued in Sant’Agata Bolognese, the Countach evolved through multiple variants, each adding wings, flares, and mechanical upgrades that gradually shifted the car from minimalist wedge to muscular 1980s icon. Factory retrospectives note that the first 152 units of the LP 400, with their unadorned fenders and clean surfaces, stand apart from the later cars that gained wider arches and dramatic rear wings as Lamborghini responded to customer demand and changing tastes. Design historians often argue that the original Countach was Lamborghini’s greatest design before subsequent modifications complicated its lines, pointing to the front bumper, the bottom of the scissors doors, the front corner of the rear wheel arches, and the center lines of the body as evidence of a carefully balanced composition that later add-ons disrupted.

Even as the Countach changed, its core ideas filtered into the broader Lamborghini lineup and the wider supercar world. The Ultimate Guide To The Lamborghini Countach, which catalogs Every Variant, Specs, Images, Performance and More, treats the model as a reference point for everything that followed, from the angular Diablo to The Lamborghini Murciélago, a sports car produced by Italian manufacturer Lamborghini between 2001 and 2010. Curated histories of The Countach emphasize that its journey is not just about one vehicle but about an approach to design that embraces risk, celebrates drama, and accepts inconvenience as the price of visual and emotional impact. That philosophy, born in the tension-filled transition from prototype to the 1974 production car, is why the Countach still feels like a living argument about what a supercar should be, rather than a relic of a bygone era.

More from Fast Lane Only:

Leave a Reply