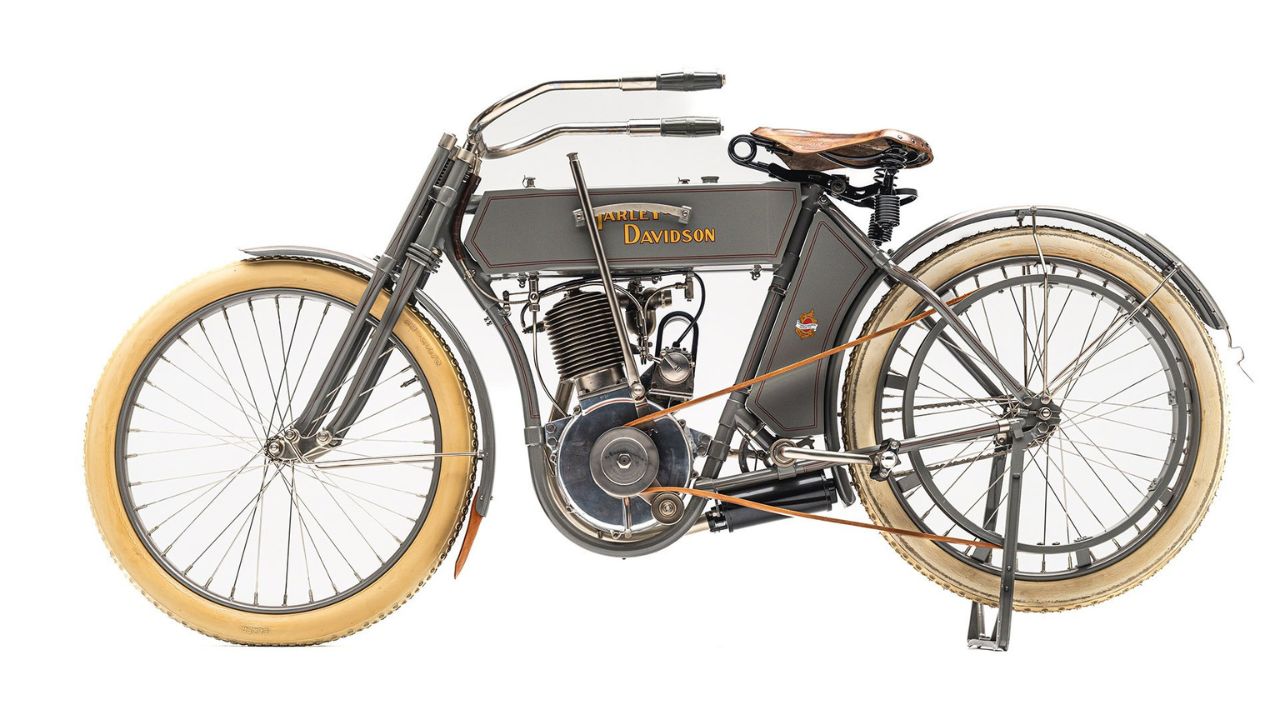

Back in 1909, Harley-Davidson wasn’t the legend it is today. They were still figuring things out, experimenting with power and design, and taking real risks. The Model 5-D was one of those risks—their first V-twin machine, aimed at doubling horsepower and proving Harley could build something more serious than a motorized bicycle.

It didn’t go perfectly. Fewer than 30 were made, and it had its share of mechanical quirks. But it lit the fuse. The 5-A set Harley on the path toward the big V-twins that would become their trademark—and change American motorcycling forever.

First V-Twin on the Streets

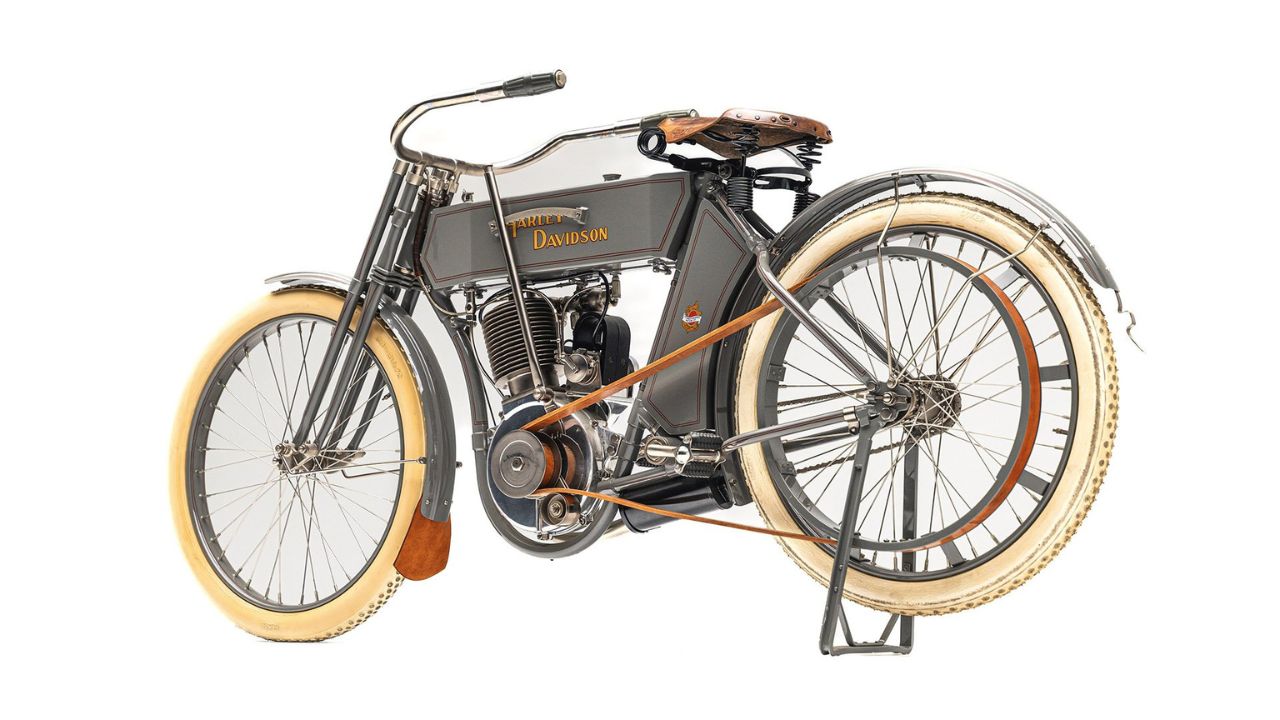

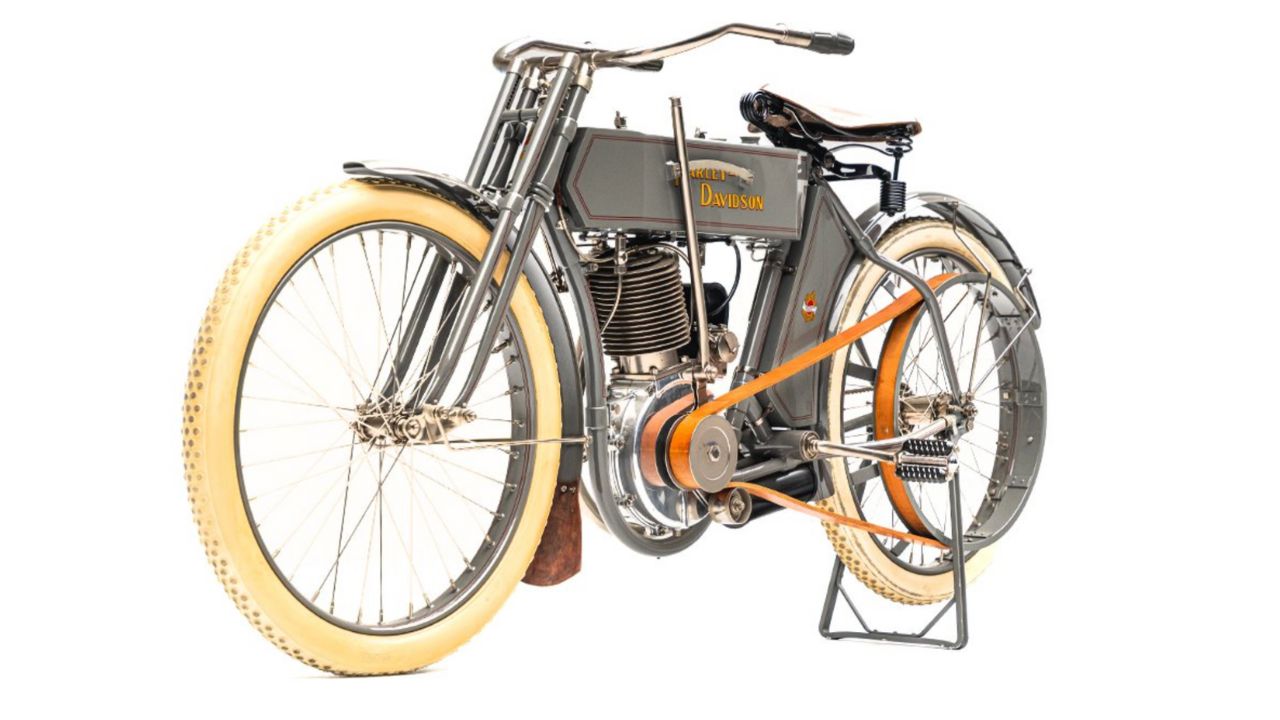

The 1909 Model 5-D was Harley’s first shot at the V-twin layout, and while it wasn’t flawless, it helped lay the groundwork. The 49.5 cubic inch (810cc) engine produced about 7 horsepower—double what their single-cylinder bikes managed. That meant more speed and more pull, even if early belt slippage was an issue.

It used atmospheric intake valves and ran total-loss lubrication. It was direct-drive—no clutch, no transmission, just a leather belt and tensioner. It wasn’t elegant, but it got the job done, and in 1909, that was enough to get attention.

Leather Belt, No Gears

Forget gears. The 5-A didn’t have a transmission, which meant starting the thing was part strategy, part workout. Riders would pedal it like a bicycle to start the motor, then control motion through a belt idler pulley that tensioned the drive belt when you wanted to move.

This setup worked, but it wasn’t exactly smooth. Riders had to kill the engine to stop and restart again to get going—fine for rural roads, frustrating in traffic. Still, it was a snapshot of a time when motorcycles were built more like pedal-bikes with engines strapped on.

Suspension? Try Your Spine

The front end of the 5-A featured a basic springer fork with a single spring and no hydraulic damping. Rear suspension? That didn’t exist yet—just a rigid frame and a padded leather seat that flexed slightly on its frame mount.

Every pothole or rut went straight through the frame into your spine. But in 1909, paved roads were rare, and most riders expected to rattle. The 5-A wasn’t built for comfort—it was built to keep rolling, which it did better than most of its peers.

Fueling Simplicity

The fuel system was gravity-fed from a teardrop-shaped tank mounted on the top tube. No fuel pump, just gravity doing the job. The tank held just over a gallon, enough for roughly 90 to 100 miles, depending on terrain and throttle use.

There wasn’t a real carburetor as we know it today—just a primitive mixing valve. Tuning it was more art than science, with riders tweaking mixture via a manual lever while riding. Primitive? Yes. But it worked, and back then, that meant something.

Wood Rims and Skinny Rubber

The wheels were 28-inch clincher bicycle rims, wrapped in narrow tires. Braking came from a simple rear coaster brake, like on a bicycle. There was no front brake at all—if you needed to stop fast, you’d better plan ahead.

Tires were narrow and pumped to high pressure, giving a harsh ride but low rolling resistance. In dry weather, the 5-A tracked straight. On loose dirt or wet wood planks, it got sketchy fast. But again, in 1909, this setup was ahead of most home-brew builds on the road.

A Saddle, Not a Seat

The 5-A used a leather saddle mounted on a springed bracket. It wasn’t much, but it softened the ride just enough to take the edge off on long trips. Riders sat upright, with a wide handlebar that swept back to the rider.

Foot controls were limited—no clutch, no brake pedal, and no footpegs. Your feet went on the pedal cranks when not used to start the engine. There wasn’t much in terms of ergonomics, but the riding position was manageable for short trips or country cruising.

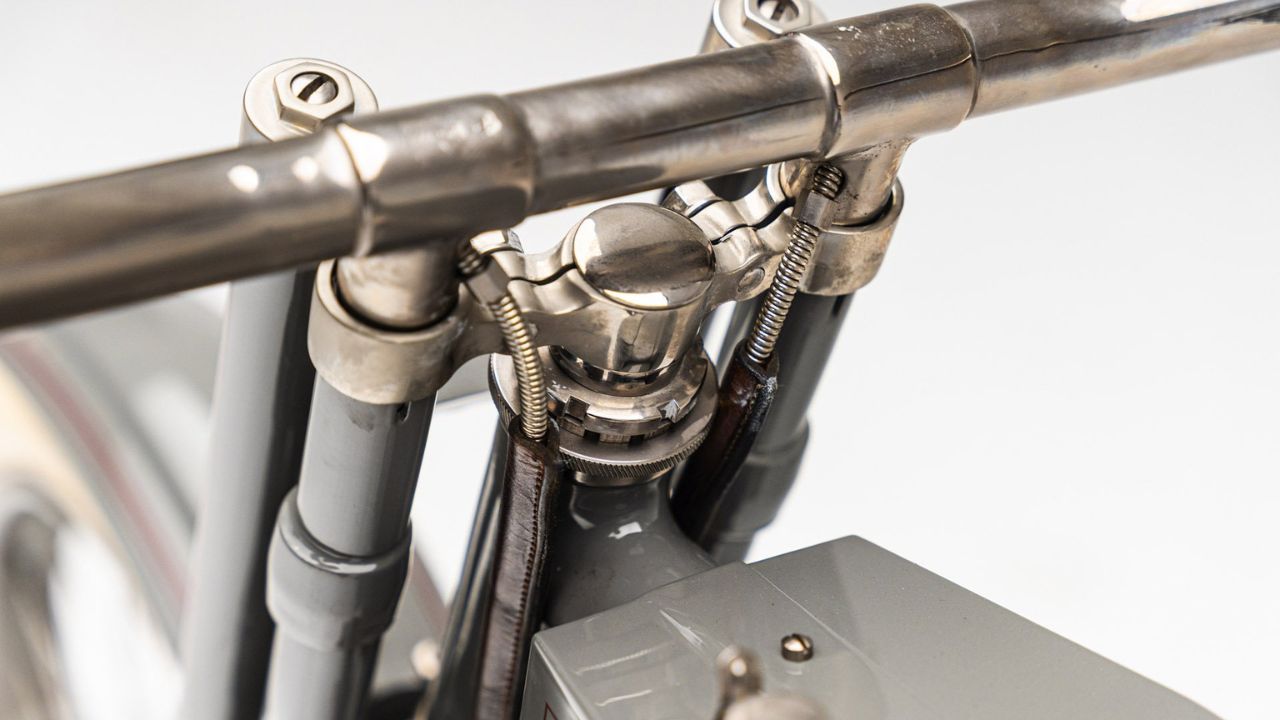

Handlebars With a Job

The handlebars did more than steer—they were your control panel. One lever handled throttle control, another adjusted ignition timing. You’d move them independently while riding to balance power, speed, and engine heat.

It sounds complicated, but once you got the hang of it, it became second nature. Riders had to be part mechanic, part operator. No dials, no gauges, just your feel for the engine and your understanding of the road. It was riding by instinct and mechanical sympathy.

Harley’s Sales Gamble

Harley only produced around 27 of the 5-A model in 1909. It was a big bet—upping displacement and complexity in hopes of offering real performance. But the V-twin didn’t catch on right away. Problems with belt tension and reliability made it a hard sell.

Still, it marked Harley’s push from motorized bicycles to real motorcycles. Even if the 5-A was rough, it helped establish the V-twin layout as Harley’s calling card. The company learned from the 5-A, refined the idea, and doubled down in the years that followed.

No Lights, No Horn, No Frills

The 5-A didn’t come with lights or a horn. If you wanted to ride at night, you’d bolt on a carbide lamp and hope it stayed lit. And if you wanted to be heard, you’d need a squeeze-bulb horn or your own voice.

That minimalism wasn’t optional—it was just how bikes were built then. It kept things light, affordable, and easier to service. And it gave riders a blank canvas to modify. Even in 1909, people were personalizing their bikes.

A Rare Survivor

Because only a couple dozen were made, the 5-A is nearly impossible to find today. When one shows up, it’s usually in a museum or private collection. Most were ridden hard and worn out long before anyone thought to save them.

But its importance is clear. This wasn’t just an early Harley—it was the beginning of the V-twin lineage that still defines the brand. It’s crude, mechanical, and tough—but that’s exactly what makes it interesting. The 5-A didn’t just roll down roads. It started something bigger.

Like what you read? Here’s more by us:

*Created with AI assistance and editor review.

Leave a Reply